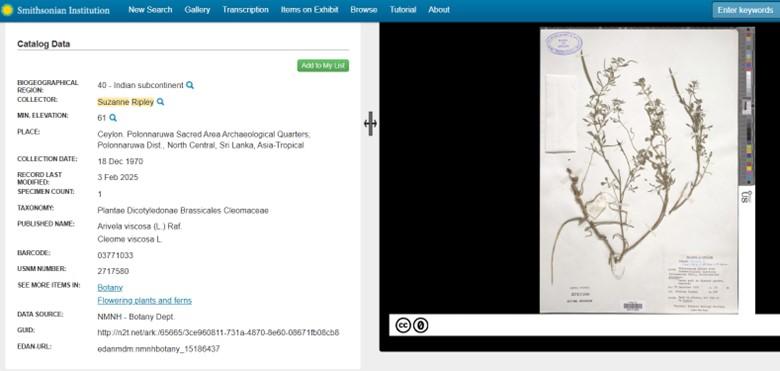

Metadata for (and image of) a botanical specimen collected by scientist Suzanne Ripley in 1970, now held at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

Imagine you’re searching online for information about Sally Ride, the first American woman to go to space. You type her name into the search bar of your favorite internet search engine, and within seconds, you’re presented with books, articles, and photos of her mission. But how did all that information appear so quickly? The answer is metadata. Metadata is like a digital map, guiding us (hopefully!) to the right places. In this case, metadata linked to articles, photos, and books about Sally Ride helps us discover her story with just a few clicks.

Metadata is, in essence, data about data: information that describes an object or document. Metadata attached to a photograph, for instance, might include details about the date it was taken, the people in the photo, or the context behind the image. In museums like those at the Smithsonian, metadata plays a key role in organizing vast collections, making it easier for researchers, students, and the public to find and access materials, especially related to overlooked or underrepresented stories such as those of women in history. In the context of a museum, metadata is a vital tool for rediscovering, preserving, and sharing history. By ensuring that women’s voices and experiences from the past are both visible and accessible, metadata bridges the gap between hidden histories and modern researchers.

Smithsonian Efforts to Share––and Uncover–– Women’s Hidden Histories

In 2023, research data scientist Rebecca Dikow, Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum digital curator Elizabeth Harmon, and a team of colleagues from across the Smithsonian published an essay called “Let the Records Show: Attribution of Scientific Credit in Natural History Collections.”1 The essay describes a multi-year collaborative project that examined the effect of incomplete metadata on our knowledge of women’s contributions to science and explored the role that digital tools could play in fixing this problem. Among the project’s findings was this strange fact: digital collections sometimes inadvertently concealed women’s contributions to science — even when they had been created to enhance access and knowledge.

Formal portrait of Mary Vaux Walcott (1860–1940). Walcott was a noted wildflower artist and photographer. Image courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives Record Unit 95 Box 24 Folder 1.

One reason for this seeming contradiction was simple human error: metadata handwritten on original paper records sometimes didn’t get transferred over to the new, digital context correctly. Metadata is “being lost,” the article’s authors observed, when information is transferred “from the paper label to the digitized occurrence” ––either “at the time of transcription” or “when transcriptions are entered into the collections database.” In several notable cases, women’s scientific contributions were erased when transcribers neglected to type in the word “Mrs.” For instance, this oversight led to the misattribution of several scientific discoveries to a man named Charles Walcott, instead of to his wife, Mary Vaux Walcott (“Mrs. Charles Walcott”). In other cases, the issue was rooted in faulty assumptions. Research conducted by a primatologist named Suzanne Ripley (often named S. Ripley in written records) was commonly misattributed in digitally transposed metadata to an ornithologist named Sidney Dillon Ripley (who served, for a time, as secretary of the Smithsonian).

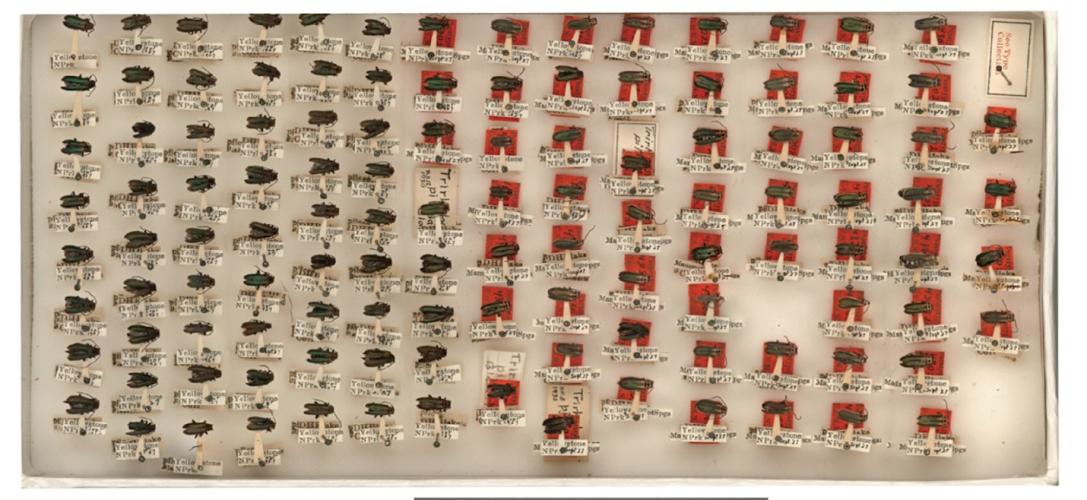

Leaf beetles collected by Doris Holmes Blake, one of the most productive beetle taxonomists at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Research conducted by Dikow and her colleagues was used to create item-level metadata that has begun to reveal her impact on the field of entomology. From Dikow et.al.,2023, “Let the Records Show: Attribution of Scientific Credit in Natural History Collections,” International Journal of Plant Sciences 184, no 5: 392-404.

Digital Strategies for Improving Metadata in Museum Collections

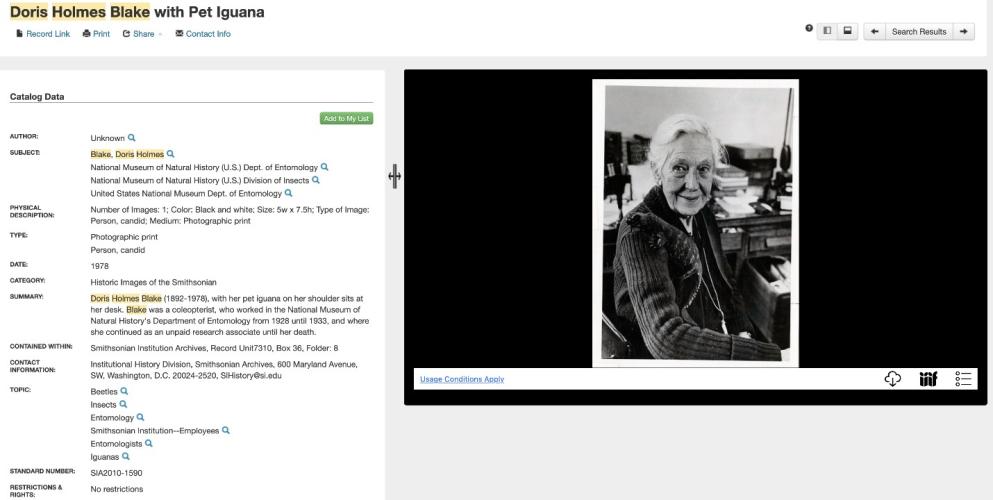

Dikow and her colleagues developed a set of digital strategies to find and remediate these sorts of errors, ensuring that women scientists such as Mary Vaux Walcott are now credited in collections metadata (and, subsequently, in scholarly articles) for their research and achievements. Still, the authors acknowledge, there are many more women whose contributions remain misattributed. In some cases, this is because the metadata attached to the paper records of the discoveries made by women scientists are listed “without first names or initials.” This, they note, is “particularly true” in the case of “women identified as ‘Miss,’ whose first names or initials are rarely included.” Other challenges result from gaps in the written record, including those caused by historical labor practices. For instance, some women scientists lost their jobs due to a Great Depression-era law (Section 213 of the 1932 Economy Act) that encouraged the dismissal of married women from federal jobs when their spouses were also federal employees. Some women who found themselves in this situation, such as a prolific entomologist named Doris Holmes Blake, could only continue their research as unpaid “volunteers” at institutions like the National Museum of Natural History. But because the Smithsonian keeps fewer records about the work of unpaid laborers, Dikow and her colleagues had difficulty recovering metadata related to research that Blake conducted after 1933.

A screenshot of the metadata in the Smithsonian online database about a photograph of entomologist Doris Blake. Metadata in the description field notes that “Blake was a coleopterist, who worked in the National Museum of Natural History's Department of Entomology from 1928 until 1933, and where she continued as an unpaid research associate until her death.”

If you go back further, you’ll discover that Dikow and her colleagues built their work on the shoulders of earlier projects––such as a crowdsourcing project developed at the Smithsonian Institution Archives (now Smithsonian Libraries and Archives) in the early 2000s. In those days, museums were only just starting to experiment with ways to share their collections online. Seeing an opportunity in the emergence of early (pre-Instagram) photo sharing platforms like Flickr, longtime Smithsonian staffer Effie Kapsalis worked with her colleagues at Smithsonian Institution Archives to use crowdsourcing strategies to improve metadata about materials in the collections. They began to share items––such as photographs––along with what little descriptive metadata they had about such items online, asking members of the public to help identify individuals depicted therein.

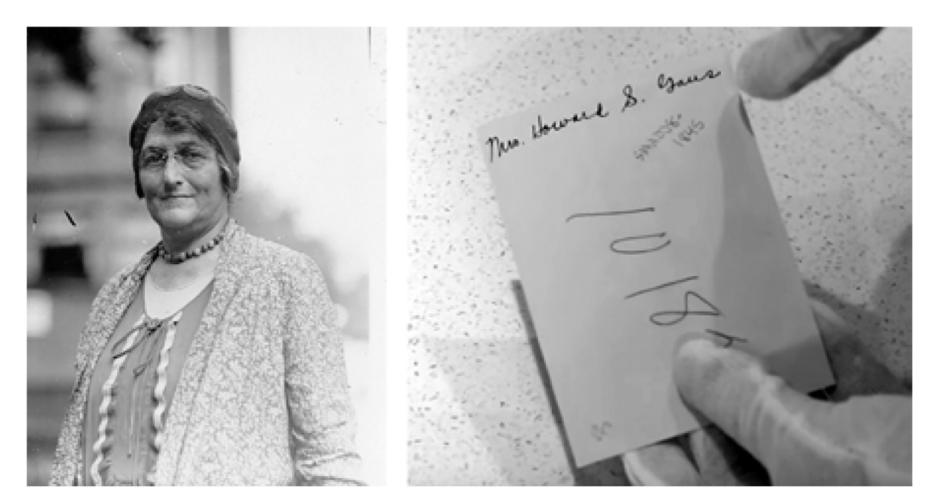

As Kapsalis reported in a 2016 article, the results of this initiative were astounding.2 Even when archivists could offer only minimal initial metadata about the subject of photographs (via, for instance, just “an initial for a first name and a hard-to-make-out last name”) volunteers were able to identify many of the individuals depicted in these photographs. The process “usually started with a hunch from one visitor, sending another off to look for a primary source in a database, library, or archive. Once the lead was confirmed or denied, visitors posted a link to their sources in the comments section.” Archivists could then use this information to “update the collection record and associated metadata with the new information and create richer biographical resources for these scientists.” In this way, they were able to identify a long list of under-recognized women scientists and scholars of various sorts with the help of crowdsourcing.

From Afterthought to Accurate Representation

Portrait of sociologist Bird Stein Gans (left), who co-founded the Society for the Study of Child Nature, the first organization in the United States to focus on the field of parent education. Image courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 90-105, Science Service Records, Image No. SIA2008-1845. The back of the portrait (right) was incorrectly identified by Archives staff as “Mrs. Howard S. Gaus.” She was correctly identified by volunteers participating in a crowdsourcing effort helmed by Effie Kapsalis and the Smithsonian Archives. From Kapsalis, 2016, “Making History with Crowdsourcing,” Collections12, no. 2: 187-197.

Among the many findings that emerged from Kapsalis’ project was the realization that wives often “traveled with and worked alongside their husbands collecting specimens for the Smithsonian; however, these women often did not receive any recognition.” Together these efforts resulted in the creation of more accurate metadata on a wide array of physical and digital items in the Smithsonian’s collections and the revelation of countless forgotten women’s histories. It also laid the foundation for Dikow and her colleagues’ later efforts.

As these initiatives demonstrate, our digital age holds a great number of pitfalls and promises as regards metadata’s power to shed light on women’s hidden histories. As museums collect more and more material (including “born-digital” materials––that is, materials that have never *not* been digital), it will be important to develop and maintain accurate collections metadata. In an age where much of our information is created, shared, and consumed digitally, accurate metadata is an indispensable tool for archivists, librarians, students, and researchers working to uncover women’s history. It is more than just a way to categorize materials—it is a tool that gives women’s activities and experiences the visibility they deserve, enabling important historical discoveries. The keywords, dates, and contextual descriptions added to each item are not just technical details; they are the means by which the histories of women are finally able to be seen, heard, and fully appreciated.

Notes:

- Rebecca B. Dikow, Jenna T. B. Ekwealor, William J. B. Mattingly, Michael G. Trizna, Elizabeth Harmon, Torsten Dikow,Carlos F. Arias, Richard G. J. Hodel, Jennifer Spillane, Mirian T. N. Tsuchiya, Luis Villanueva, Alexander E. White, “Let the Records Show: Attribution of Scientific Credit in Natural History Collections.” International Journal of Plant Sciences, volume 184, number 5, June 2023.International Journal of Plant Sciences, volume 184, number 5, June 2023.

- Effie Kapsalis, “Making History with Crowdsourcing,” Collections: A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals, Volume 12, Number 2, Spring 2016, pp. 187–198.

Further Reading:

Celeste Brewer, “Eleanor Roosevelt Speaks for Herself: Identifying 1,257 Married Women by their Full Names,” Columbia University Libraries Blog, Sept. 9, 2020.

New Partnership Illuminates Hidden Record of NASA’s Human Computers

Discoverability Lab Offers New Look at Historical Data and Machine Learning

By Rachel Mattson, archivist, public historian, and senior consultant at Educopia.