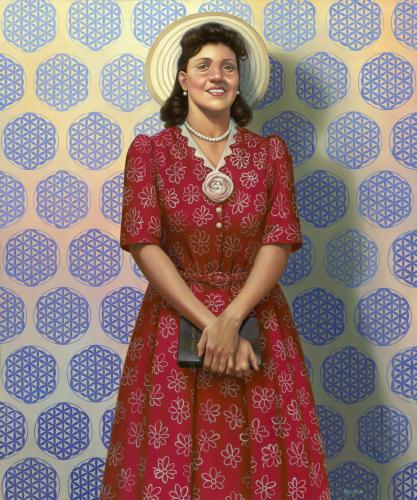

Henrietta Lacks (HeLa): The Mother of Modern Medicine, 2017. Painting by Kadir Nelson, American, born 1974. Collection of the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery and National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift from Kadir Nelson and the JKBN Group LLC.

Henrietta Lacks, a Virginia tobacco farmer who died at age 31, left a legacy unparalleled in modern medicine: cells that have lived for decades, contributing to scientific breakthroughs and helping thousands of patients with polio, AIDS, Parkinson's and many other diseases.

A unique figure in American history, Lacks is being recognized this month at the National Portrait Gallery, with the installation of a 2017 portrait by artist Kadir Nelson. The portrait was jointly acquired by the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of African American History and Culture and will be shared by the two museums.

Lacks, the great-great-granddaughter of a slave, lost her life in 1951 to cervical cancer. During her treatment, cells were taken from her body without her knowledge or consent. Upon her death, doctors discovered that these cells lived long lives and reproduced indefinitely in petri dishes. These "immortal" cells have since contributed to more than 10,000 medical patents, aiding research and benefiting patients across the globe.

Rebecca Skloot's best-selling 2010 book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, and a subsequent HBO film examine Lacks' legacy and related questions about medical ethics, privacy, race and women's roles.

"The National Museum of African American History and Culture has always felt that the story of Henrietta Lacks is a significant and important moment that deserved greater recognition," said Lonnie Bunch, director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

"The National Portrait Gallery brings those whose stories have been excluded or who exist on the margins of history to the center," said Dorothy Moss, curator of painting and sculpture, National Portrait Gallery. "Henrietta Lacks' portrait allows us to open dialogue about her contributions to modern medicine and raises questions of ethics related to the long history of medical experimentation on those deemed powerless. It is a story that each of our visitors, including the thousands of schoolchildren who enter our museum, should know."

Nelson's portrait of Lacks makes several references to her contributions to medical science: The wallpaper features the "Flower of Life," a symbol of immortality; the flowers on Lacks' dress recall images of cell structures; and missing buttons allude to the cells taken from her body without permission.

Lacks' portrait will be on view at the National Portrait Gallery through Nov. 4, 2018.